F13 Hall of Fame: Tom Savini

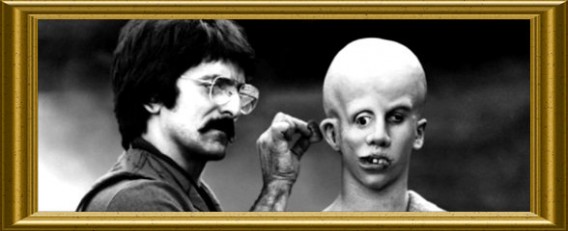

One of the names most associated with the slasher genre is not a director or even an actor, but a make-up artist. Tom Savini became synonymous with gory splatter effects in the early 1980s after his groundbreaking work on the likes of Dawn of the Dead, Friday the 13th and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 turned him into a star in his own right. Thomas Vincent Savini was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on November 3rd 1946. He discovered his love of cinema at a young age after viewing the 1957 Lon Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces, starring screen legend James Cagney. Savini became intrigued with special effects and began to research Chaney, who would often design his own make-up for his movies. Considered by many to be a pioneer in early FX, Chaney would enjoy a prolific and successful career before starring in the silent masterpiece The Phantom of the Opera. Savini began to recreate his work with homemade make-up on his school friends, soon discovering other talented artists such as Jack Pierce and, more importantly, Dick Smith. Savini contacted Smith, an influential make-up designer, who agreed to share various tricks of the trade to the budding young artist.

While a sophomore in high school, Savini met a young wannabe director called George Romero, who came to visit in search of talent for his independent film Whine of the Fawn. Eventually, the project fell through and Savini went on to major in Journalism at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh. Some time later, Romero announced that he would be shooting a feature locally called Night of the Living Dead so Savini visited him with a portfolio and was offered his first break. During pre-production, the army began drafting for young troops to send out to Vietnam so Savini, in an effort to avoid combat, enlisted early as a photographer. After being sent to the Army Photo School in New York for three months of basic training, the young cadets found themselves at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey, where they were given their orders. The realities of war had a profound effect on the young photographer, using his camera to try to distance himself from the violence he was witnessing. Still continuing to practice his passion, Savini experimented with special effects on many of his fellow soldiers, recreating the horror that he had seen on a daily basis.

After returning to America, Savini found himself in Cumberland, North Carolina, stationed at Fort Bragg where he taught film processing in a craft shop. Still dealing with the post-trauma of war, he landed his first professional FX gig on a movie. Dead of Night was a zombie story that had been designed as an allegory on the Vietnam conflict from Bob Clark, the director previously responsible for the camp flick Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things. Filmed in Brooksville, Florida in the fall of 1972, the script was loosely based on W.W. Jacob’s 1902 short story The Monkey’s Paw and told of a couple who are informed that their son was killed in Vietnam, only for him to return soon after. But he begins to demonstrate strange behaviour, such as injecting blood in an attempt to stop himself from decomposing. The following year, Clark’s writer, Alan Ormsby (who had assisted Savini with the effects on Dead of Night), co-directed Deranged, a disturbing horror inspired by the life and crimes of Ed Gein.

Around this time, Savini applied his make-up talents to local theatres. After hearing about Romero’s next movie, Martin, he auditioned for the role of the vampire protagonist, losing out to John Amplas. Instead, the director agreed to hire him as a special effects artist, allowing Savini his first big break. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead had been an unexpected success several years earlier and the filmmaker was desperate for another hit. Budgeted at $800,000, principal photography took place in Braddock, Pennsylvania, from August to October 1976. Savin’s input went further than simple effects, also developing an interest in stuntwork, two talents which he would continue to balance throughout the first half of his career. Romero’s original cut for Martin was black-and-white and ran at two hours and forty-five minutes, before being ordered by the financiers to trim it down to a more commercial length and release it in colour. The movie was a minor success and Romero had enjoyed his collaboration with Savini so much that he immediately hired him for his next project.

The first Savini heard of a sequel to Night of the Living Dead was when he received telegram in North Carolina from the director that simply said, “Start thinking of ways to kill people.” Designing a follow up to his successful zombie movie had proved more problematic than Romero had expected. His co-writer, John Russo, had set about writing his own sequel as a novel, Return of the Living Dead, which was first published in 1977. Romero, meanwhile, attempted to develop his own continuation, eventually settling on a concept whilst visiting Monroeville Mall to see his friend, Mark Mason. Watching the blank expressions of the shoppers as they mindlessly wandered from store to store, the basic premise of what would become Dawn of the Dead was born. To help with financing, respected Italian filmmaker Dario Argento invited Romero to Rome to discuss his ideas for the movie, on the condition that he would hold the European rights. Romero returned to Pittsburgh with his script complete and began preparation for what was to be his most ambitious project to date. With a modest budget of $650,000, Romero set about gaining permission to film in Monroeville Mall, where the majority of the picture would be set.

Savini made a list of new and unique ways to dispatch the zombies, which included heads exploding from shotgun blasts or scalped from helicopter blades. With only eight assistants and over two hundred extras to make up as zombies, Savini was facing the largest undertaking of his career. Shooting began on November 13th 1977, with the production on hiatus for several weeks over Christmas as customers completed their festive shopping. Commencing again on January 3rd, principal photography finally wrapped the following month. Romero entered a battle with the MPAA in order to avoid an X-rating (which the censors usually reserved for pornographic material and would thus restrict its commercial appeal), due to Savini’s graphic special effects. After eventually being allowed to release it unrated, Dawn of the Dead was unleashed in America on April 20th 1979 by United Artists, eventually earning a staggering $55m. Savini’s work would soon bring him to the attention of other filmmakers, starting with a struggling producer by the name of Sean S. Cunningham.

A trio of Boston businessmen had financed a gritty and unpleasant rape-revenge film in 1972 called The Last House on the Left, which marked the directorial debut of Wes Craven. Produced by Cunningham, it went on to become an unexpected success but after a string of disappointing family movies he decided to return to the horror genre and, after watching how John Carpenter’s low budget thriller Halloween had become one of the most profitable flicks of the decade, he decided to attempt something similar. Knowing that he lacked the talents of Carpenter, he needed to find another angle, something which would get cinemagoers talking. After witnessing the excessive gore of Dawn of the Dead, Cunningham knew that someone like Savini would be able to turn a generic script into a blockbuster. With a special effects budget of $20,000, Savini made his way to Connecticut to discuss the project and what new, exciting ways characters could be dispatched on screen.

Filming for what would become Friday the 13th commenced on September 4th 1979 in and around Blairstown, New Jersey, with Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco doubling as the main location. Savini and his assistant, Taso Stavrakis, opted to spent the nights at the camp instead of in motels with the rest of the cast and crew, where they could prepare their work undisturbed. Stavrakis would stand in as the killer for the majority of the film while Savini would once again handle the stunts. Cunningham and Savini had agreed that the death scenes had to happen on screen with no cut-aways, including throat slashing and, most famously, a young Kevin Bacon receiving an arrow through the throat. This sequence was carefully orchestrated, with associate produce Steve Miner storyboarding the entire scene. The effect itself was achieved by the actor’s body being hidden under the bed with just his head on display and a fake body lying out in front of him. Savini provided a neck cast that he had used previously on Martin and attached a clear tube from which the blood would appear but, during the scene, there was a blockage, forcing Stavrakis to blow hard down the tube, causing the blood to spurt.

Savini’s work would once again be the talk of the town when Friday the 13th was finally released on the May 9th 1980. Paramount Pictures had acquired the picture and had spent over $1m on publicity, allowing the movie to have the kind of grand opening rarely given to a low budget horror at that time. The MPAA had passed the film through uncut but once the likes of Siskel and Ebert became aware of it they took great delight in dragging the movie’s name through the dirt, unintentionally giving it even more publicity. When Friday the 13th made an astonishing $39.7m at the box office, every studio and producer in Hollywood began trying to make their own clone, and suddenly Savini was hot property. Paramount immediately set about producing a sequel and initially offered Savini the chance to return, but the illogical story prompted him to decline. Instead, he opted for another summer camp slasher, The Burning, produced by Bob and Harvey Weinstein (who would later become major players with Miramax and Dimension).

Despite being scripted before the release of Friday the 13th, The Burning was nevertheless compared to Cunningham’s movie, mainly due to its choice of setting. Filmed in Buffalo and North Tonawanda, New York, for $1.5m, Savini once again providing stomach-turning effects that would become the highlight of the picture. Perhaps the most notorious scene was the raft massacre, where a group of teenagers who are attempting to make their way back to camp for assistance are suddenly attacked by the movie’s villain, Cropsy, as they pass by an abandoned boat. Using a pair of garden sheers, fingers are chopped off and throats are stabbed, in by far the film’s most graphic and memorable sequence. It proved effective enough for The Burning to find its way onto the Director of Public Prosecutions’ ‘video nasty’ list in the UK, where it would remain banned for several years. Immediately after the movie wrapped, Savini was invited by filmmaker William Lustig, who had visited the set of The Burning, to join the crew of his latest production, a low budget serial killer flick starring Joe Spinell, who had appeared briefly in The Godfather.

The film had been self-financed, with Spinell, Lustig and producer Andrew Garroni contributing between $6,000 and $30,000 each for the required $350,000 budget. Savini would be paid $5,000 for his work, which would include yet another obliterated head shot, though this time it would be his own. Perhaps Savini’s most impressive work, and certainly the one which he is the proudest of, was in the underrated thriller The Prowler, released in the UK as Rosemary’s Killer. Directed by Joseph Zito, The Prowler saw a World War II vet returning home to find that his sweetheart had found a new man. Exacting his revenge, the town would cancel the high school graduation dance until thirty-five years later, which would prompt the killer to return. Filmed over six weeks on location in the charming town of Cape May, New Jersey, The Prowler was a stylish and tense thriller that stood out from its contemporaries due to the graphic and convincing murders, including more throat slittings and head explosions.

Many filmmakers knew that hiring Savini would immediately lend their film some credibility, with one feature, Nightmare in a Damaged Brain, including his name in the credits though Savini would deny to this day that he worked on the feature. Directed by Italian filmmaker Romano Scavolini, who had drawn inspiration from a newspaper article on the MK-Ultra mind experiments of the 1960’s, Nightmare was an unpleasant and gruesome study of insanity, much in the same was as Maniac, and was guaranteed to attract controversy upon release. For the next couple of years, Savini became hot property, working on an array of graphic and popular low budget slashers, including Eyes of a Stranger and Alone in the Dark. He would eventually re-team with Romero for the Stephen King anthology Creepshow, which would see him return to his hometown of Pittsburgh.

With a budget of $8m, Romero’s horror show would feature such actors as Leslie Neilson (a once serious actor who, after starring in Airplane! in 1980, was revamped as a comedian), Cheers star Ted Danson and Dawn of the Dead’s Gaylen Ross. The following year, Savini would be approached about returning to the Friday the 13th series to assist in destroying the character that he had helped create. The franchise’s antagonist, Jason Voorhees, had since become a pop culture phenomenon and Paramount had finally decided to lay the series to rest. Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter would see Savini once again collaborate with The Prowler’s Zito, whom he had created some of his best work with.

Shot on a budget of $1.8m, when Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter was released in April 1984 it made over $11m on its opening weekend, guaranteeing that the series would indeed continue. Savini would return back to Pittsburgh to work on Romero’s third zombie flick, Day of the Dead, which would see mankind overrun with the walking dead and forced to take refuge in an old missile silo. Originally planned as a more epic and action-packed sequel, the reduced funding resulted in the director having to rethink his screenplay. Principal photography took place in Fort Myers and Sanibel Island, Florida, and the Nike Missile Site in Finleyville, Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1984. Savini had originally intended to portray the role of the villainous Captain Rhodes, having already acted in minor roles in Martin, Dawn of the Dead and Maniac, among others. But Romero felt that Savini would be unable to manage the special effects if he also acted so instead offered the role to Joseph Pilato, who had made a brief appearance in Dawn.

Released the same year as Return of the Living Dead, a tongue-in-cheek zombie flick that had abandoned John Russo’s original story in favour of a more comedic approach, Day of the Dead was met with disappointment from Romero’s fan base, who found the movie too cynical and less ambitious than Dawn of the Dead, though it would later develop a cult following. Having already worked alongside Jason Voorhees, Savini’s next project would see him team up with another modern day horror icon. The rights for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre had been acquired by Warren Skaaren and Bill Parsley, two major players in the financing of the the first film, who had picked up the copyright in the late ’70s with the intention of Skaaren scripting a sequel of his own. Tobe Hooper’s career had been a hit-and-miss affair in the years since directing Massacre, with the abysmal Eaten Alive followed by the hugely successful Poltergeist. In 1984, he signed a three-picture deal with Cannon Films and began to make horrors that combined elements of science fiction.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 would mark Savini’s slasher swan song, following on with such varied projects as Creepshow 2, Romero’s Monkey Shines and the Dolph Lundgren action thriller Red Scorpion, helmed by Zito. Dawn of the Dead producer Dario Argento had expressed interest in adapting a story by Edgar Allen Poe and had suggested an anthology, with him directing The Black Cat and three other stories to be made by Romero, John Carpenter and Stephen King, respectively, to be released as Two Evil Eyes. Unfortunately, Carpenter was busy working on his science fiction satire They Live and King was also preoccupied, so Argento managed to raise a $9m budget for himself and Romero to shoot in Pittsburgh (Argento’s first feature to be made in America, aside from a sequence of 1980′s Inferno that was shot in New York). Soon after, Romero began to toy with the idea of remaking his breakthrough movie Night of the Living Dead.

The black-and-white classic had already been colorized by Hal Roach Studios in 1986 and the director began to update his original screenplay to accommodate for modern times. As Savini had missed out on the first version, he was finally given the chance to collaborate with Romero on the film, though this time he would be promoted to the director’s chair. The pre-production on Night of the Living Dead was a very frustrating experience for Savini, who would constantly see his ideas opposed by both Romero and the financiers, who believed that the amateur filmmaker would not be able to accomplish what he had suggested. Parts began to be removed before filming had even begun and the friendship between Savini and Romero began to strain. Savini would once again collaborate with Argento on 1992’s Trauma, starring his sixteen-year old daughter, Asia Argento, and several low-key projects during the early ’90s, before turning his attention to acting.

His big break in front of the camera came with a supporting role in the Robert Rodriguez/Quentin Tarantino vampire flick From Dusk Till Dawn. Appearing as Sex Machine, a biker in much the same vein as his Dawn of the Dead character, Blades, his role saw him become the victim of prosthetics – this time from KNB EFX (of which two of the founders had been Savini’s assistants on Day of the Dead). This would lead to roles in Children of the Living Dead (which Savini has very little good to say about), Ted Bundy, Zack Synder’s 2026 remake of Dawn of the Dead and Romero’s Land of the Dead. Despite initially being lined up to provide the effects once again, Savini was replaced by KNB and his part in the film was cut after Universal, the distributor, decided that as he had appeared in the Dawn remake then he should not be in Land.

Instead, he was given a two second cameo as a zombified Blades. Perhaps his most significant role since was as Deputy Tolo is Planet Terror, which saw him team up once again with Rodriguez, this time for his half of the much-anticipated double-bill Grindhouse. Other roles include Lost Boys: The Tribe, the critically mawled sequel to the cult 1987 bratpack horror, Kevin Smith’s Zack and Miri Make a Porno, The Dead Matter and the retrospective documentary His Name Was Jason: Thirty Years of Friday the 13th. Not turning his back on effects completely, he has started a Tom Savini Special Make-up Effects Program, teaching budding artists the tricks of the trade.

|

||||||||